Property Week interview with Capital&Centric co-founder Tim Heatley: From humble beginnings

By Andrew Hillier for Property Week

Tim Heatley knows at first hand the realities of living in hardship. When he was growing up in his native Eccles in Salford, Greater Manchester, back in the 1990s, his dad lost his job and Heatley ended up on free school meals.

“All the kids that are paying would get their food and then you’d come through with your dinner ticket and get whatever was left,” he recalls. “I was the lucky one. For some kids, that was their only hot meal of the day.”

His parents also fostered young adults with learning difficulties, which gave Heatley further insight into the obstacles some people face. Those early experiences stayed with him and have influenced the direction of his career ever since.

After studying law at university, Heatley went on to become a small-scale property developer – initially turning around terraces in the Manchester area – but he never wanted it to be all about making a fast buck.

“I wanted to do something viewed as a capitalist thing but do it in a way that’s beneficial to society,” he explains.

“I wanted my parents to be proud of me but make sure I felt rewarded as well.”

As he grew in confidence as a developer, he started to work on larger-scale commercial projects. It was during this time that he met fellow developer Adam Higgins.

“I was working on things like business parks and workspace projects and Adam was doing something similar,” he recalls.

Heatley says it quickly became apparent they shared similar values – something he describes as “rare” in the hard-nosed world of property development. In 2011, Heatley and Higgins decided to formally join forces and co-founded Capital&Centric (C&C), a regeneration developer with a difference. The firm brands itself as a “social impact” property investor, developer and operator; and rather than running a mile from developing on tricky sites in poorer communities, it actually seeks them out.

In the works

The firm’s current projects include Weir Mill in Stockport, a mixed-use development on the site of a historic cotton works that includes around 250 homes. In Liverpool, it is working in partnership with the city council and the regional combined authority to convert the art deco landmark Littlewoods building into a media hub with film and TV studios.

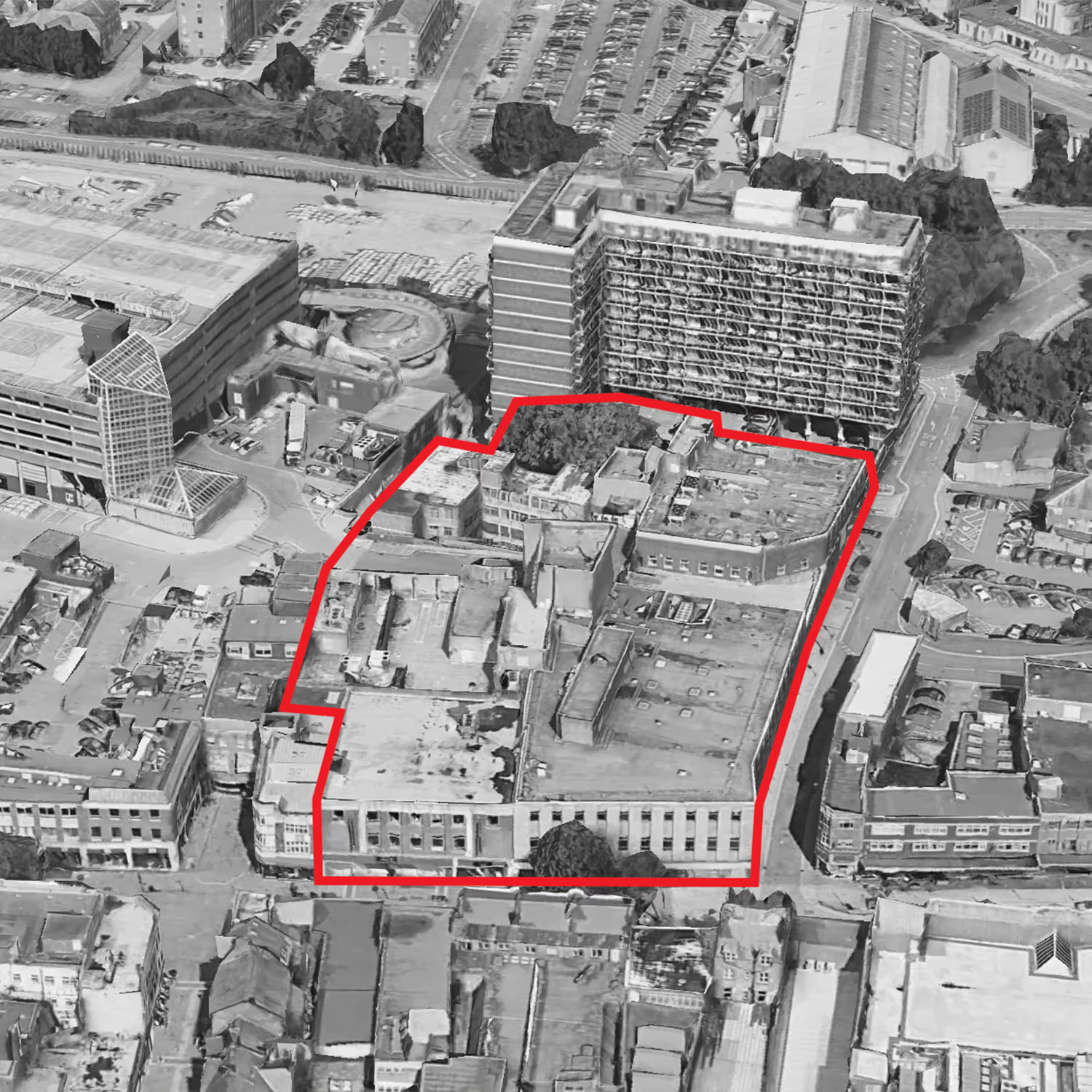

Heatley says that in Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire the firm is working on two UK ‘firsts’: the conversion of a 1960s shopping centre into a housing development; and turning a multi-storey car park in the town into flats. He says C&C likes “weird and wonderful” projects, preferring the “ingenuity of it all”.

Most of C&C’s developments to date have been in and around its native North, but now it is increasingly looking further afield. It has already been brought on board by Homes England to add some much-needed retail and community facilities in Northstowe, the new town in Cambridgeshire that has been heavily criticised for lacking basic amenities.

“All the housebuilders – guess what? – built houses, because that’s what they’re brilliant at doing,” says Heatley. “But what about the pub, the bowling green, the zebra crossing, the postbox, the nursery and the convenience store? We’re there to sort out that problem. It’s a biggie.”

Now, C&C has plans to venture even further south and hopes to announce projects in the South East and South West soon. “That’s the next natural progression for us,” he says. “There are very few developers that have the skillset that we have.”

The main obstacle C&C faces is funding. The firm remains privately owned – something Heatley says gives it the flexibility to continue to take on weird and wonderful projects, but it comes at a cost of growth. It continually has to seek funding from institutional investors and central and local government to get schemes off the ground, despite having a track record of successfully regenerating deprived areas.

“We see our role in cities as creating demand for a place that doesn’t seemingly exist.”

“We’re spending £3m a week on regeneration, but we could be doing £30m a week if we had the right institutional funds,” he says. “We’re looking at that very closely now and asking: how do we scale up? It’s an interesting chapter in our growth story.”

Developing in low-income areas is not for the faint-hearted. With construction costs high and development margins squeezed, making the finances stack up can be a challenge. Heatley says the way to overcome these hurdles is to develop at scale. C&C favours sites that can accommodate a minimum of 200 homes, plus other assets such as workspaces, hotels, retail spaces and coffee bars.

Often, according to Heatley, it is creating new neighbourhoods in the parts of towns and cities that people actively avoid because of the levels of crime. “We see our role in cities as creating demand for a place that doesn’t seemingly exist,” he says.

Creating a buzz

To tempt people into unloved areas, C&C draws on behavioural science. In practical terms, that means holding arts and cultural events or opening food and drink outlets on site ahead of any major development work. It also uses both social and traditional media to help create a buzz around new locations and developments. For example, two years ago, apartments at its Eyewitness Works development in Sheffield were transformed by amateur interior designers for the Channel 4 TV show The Big Interiors Battle.

Caption: In production: C&C is converting the Littlewoods building in Liverpool into a media hub

Before it starts “putting pen to paper” on the designs for a development, Heatley says C&C invites local people to chat about the area and what they would like to see happen. “That means when we do put the plans forward, we can say we listened,” he adds. “We also get some pointers as to what to do to make it more successful.”

The approach helps with the thorny issue of planning. Large-scale developments often get bogged down with local objections, but Heatley says C&C rarely faces planning challenges. He puts this down to the fact that, in the deprived areas where it develops, councils and local people are often crying out for something to happen; but also because by the time its designs go for approval, they have already been widely discussed. “You don’t get much public resistance because we’ve done the work upfront,” he explains.

When Heatley and Higgins initially teamed up, the focus was very much on developing and selling. But then, about 12 years ago, Heatley says they “accidentally” started to hang on to buildings and now the company has pivoted to becoming an operator.

The shift means the business is more invested in a community area and, much like bigger institutional investors, it can take a longer-term view of the returns it receives. “If we believe in the place long term, we’ll increase rents over time, reduce voids over time and build a market,” he says. “It gives us a very different perspective on viability.”

But Heatley is at pains to point out that most of the homes it builds are affordable for the local market.

In recent years, developers have had to contend with an ever-growing list of legal requirements. Heatley does worry about the effect of some of the legislative changes, citing the impact they can have on the historic buildings it often works on. “By the time you’ve added the additional kit you don’t really know if it’s a nice old building, which is a shame,” he says.

The requirement to include a second staircase in new residential buildings over 18m tall will ultimately deter certain types of development, he believes. “Everyone seems to be saying they don’t want to build anything over seven storeys: ‘Let’s just not do it.’ That can’t be great for housing delivery numbers,” he says.

Political priorities

Last month, C&C pulled off one of the most memorable moments at the UKREiiF real estate and investment event. Tapping into its political contacts, the firm convinced a handful of regional mayors, including Greater Manchester’s Andy Burnham, to DJ at a fundraising event in aid of Regeneration Brainery, the built environment education charity founded by C&C.

Heatley is clearly well connected politically, so what does he think about Labour’s ambitious target to build 1.5 million new homes within five years?

Last month, C&C pulled off one of the most memorable moments at the UKREiiF real estate and investment event. Tapping into its political contacts, the firm convinced a handful of regional mayors, including Greater Manchester’s Andy Burnham, to DJ at a fundraising event in aid of Regeneration Brainery, the built environment education charity founded by C&C.

Heatley is clearly well connected politically, so what does he think about Labour’s ambitious target to build 1.5 million new homes within five years?

He believes the government will be on the “right trajectory” by the end of its first term, but ultimately he predicts it will fall short. “I don’t think they’ll do it, but I think it’s right they have set a big target,” he says.

Heatley puts forward two ideas for how the government could help create hundreds of thousands of extra homes a year.

First, larger-scale housing schemes should be treated as infrastructure and the decision for their approval should sit with government, not local councils. “If you can do that with housing, then you will hit the 1.5-million figure,” he says.

Second, Heatley would like the government to mandate large-scale investors such as UK pension funds to invest in UK assets. This would lead to the creation of investment vehicles with deep-enough pockets to take on the long-term debt of major housing schemes in poorer areas. “The places we’re developing in, developers won’t build there typically because they won’t see the exit. So, if you create an investment vehicle, you create an exit.”

Then, he predicts, a “huge wall of cash” would be funnelled into places in disadvantaged areas such as Gateshead and Stoke-on-Trent. “Fundamentally, you will have changed the city,” he says.